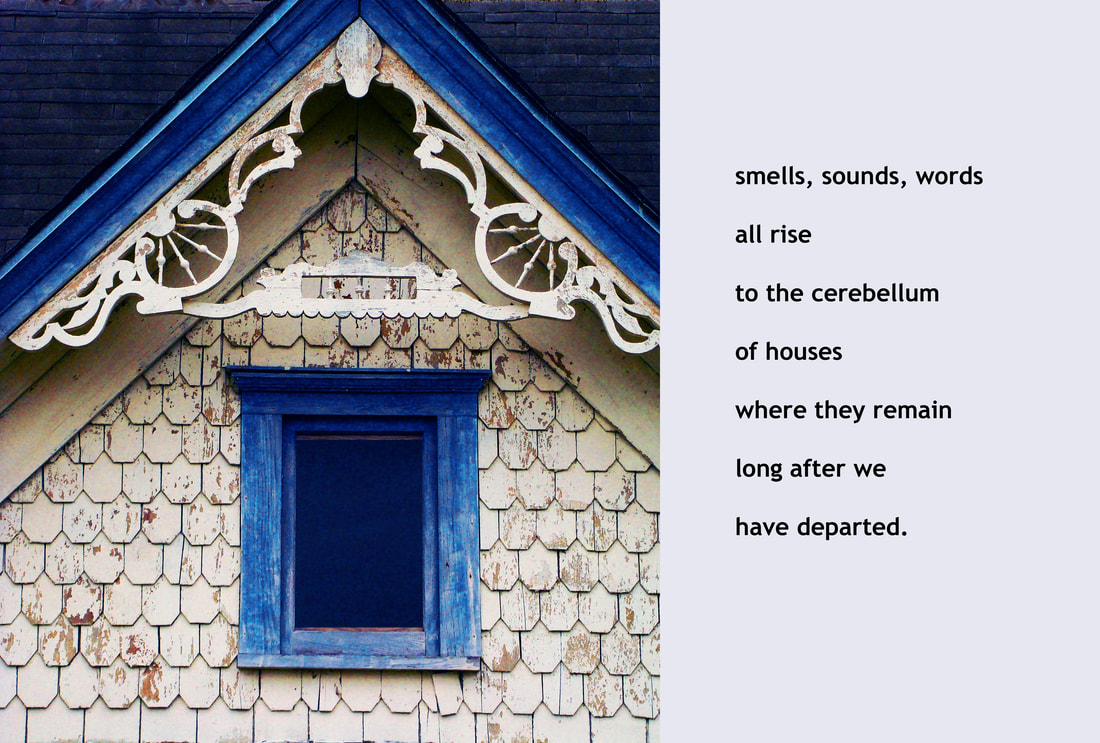

The Attic

Hybrid by Christopher Woods

“I like to combine words and images in picture poems.”

Christopher Woods is a writer and photographer who lives in Texas. His monologue show, Twelve from Texas, was performed recently in NYC by Equity Library Theatre. His poetry collection, Maybe Birds Would Carry It Away, is forthcoming from Kelsay Books.

https://christopherwoods.zenfolio.com/f861509283

https://christopherwoods.zenfolio.com/f861509283

One Sentence

Non-fiction by Megan Hanlon

He said it at the lunch table. Even small earthquakes send wide ripples.

His words floated through the heavy air, were tossed back and forth among a student body that was already writhing in pain. By the final bell, the whole high school had heard it. Unconnected groups, united by a shared enemy, waited for him in the common area near where he had said it.

Her fellow cheerleaders and friends, still raw in their grief and shock, stared at him with derision. Meaty football jocks threatened to punch his face bloody. The "kickers" - FFA and 4H devotees who wore cowboy boots to class - offered to launch heavy ropers into his ribs.

The principal pulled my brother away from the trembling crowd, stuck him in an office, and called the police. The police delivered him home.

After he said it, maybe his friends cringed and chuckled and hurried to change the subject. Maybe they thought it was a harmless joke and guffawed with disgusting amusement. I don't know. I only lived through the aftershocks.

He said it on a Thursday or a Friday, but the rumbling didn't quiet for months. Seeking vengeance and power where they had none, teenagers (and a few adults) drove up and down our street to glare at our dirty living room windows.

Some stopped before our gravel driveway then gunned the gas, tires screaming their disdain. A few parked defiantly and waited in menacing silence.

I was 12, and hadn't known terror until then.

For weeks we only slipped out of the house when necessary, and kept our heads down. All of us save my dad were afraid of being stalked through the grocery store, run off the country roads, even shot at by guns that usually came out only during deer season. I swam alone in the thick disgrace of being from that family, the one with the kid with the smart mouth in a small town.

I doubt anyone was surprised he said it. My dad, never particularly respectful toward the opposite sex, had said things like that - though not as vile, and rarely in public. I remember his elbowing a fellow grease monkey at the service station when either of them saw a woman, and their back-and-forth stage whisper of “creamy juicy thighs!” He and my brother shared a running joke: "The best part of you ran down your mother's leg." "It's not my fault you missed."

My mother would say nothing. I turned crimson.

After he said it, I had to fake normalcy and perform jolly Christmas tunes for my seventh-grade band concert in the high school gym. My brother couldn't come - school officials said don't bring him back any time soon, we can't guarantee his safety - and he couldn't be left unprotected. As my parents and I loaded into our sputtering car, he crawled up the folding stairs into the attic space of our shabby rental. There he hid between the splitting rafters, alone, armed with nothing but a 13-inch black and white TV to watch while he waited for our return.

On the short drive home, fear painted pictures of the smoking remains of our house burned to the ground, or broken glass and blood on the termite-bitten floors. Whether the police and firefighters would have turned a blind eye in her name, I don't know.

After he said it, I don’t remember, but there must have been a funeral, because she was buried in Palms Memorial Cemetery south of town. There was a trial, too, where her father said he was not guilty of violating his daughter. The court sentenced him to 20 years.

After he said it, my brother never went back to that high school. He enrolled in the next town over and showed up for one more year before dropping out. Rusty trucks hung with gun racks still rolled by the house, still tailed him around town occasionally. I had to share a school with her younger sister, a grade above me, for three more years.

After he said it, her sister confronted me in the middle of the junior high, where pre-teens tumbled down the halls like rocks in a landslide.

"By the way, I don't like your brother very much," she sneered at me. What could I say? We can’t choose the families we come from.

After he said it, the fear faded out, but the shame remembers.

Megan Hanlon is a podcast producer who sometimes writes. Her words have appeared in Write or Die Magazine, Variant Literature, Gordon Square Review, and other publications both online and print. Her blog, Sugar Pig, is known for relentlessly honest essays that are equal parts tragedy and comedy.

X: @sugarpigblog, FB: @sugarpigblog & Bluesky: @sugarpigblog

http://sugar-pig.blogspot.com

X: @sugarpigblog, FB: @sugarpigblog & Bluesky: @sugarpigblog

http://sugar-pig.blogspot.com